Sunday, December 16, 2007

Leg Three

A couple days ago Alisa suggested that we skip over Ensenada, a town of 200,000 people just sixty miles south of San Diego and the most common place for southbound yachts to clear into Mexico. Instead we are planning on sailing the 330-odd miles to Isla Cedros, where there is also an official Port of Entry. We just don’t have the nerve to face another big town right now.

So that’s the plan. Alisa made us cheeseburgers and fries last night for our last dinner in U.S. waters. Forecast winds are very light, so it will likely be a slow passage. But the nights should be a little warmer that far south, and the village on Cedros should be a pretty peaceful place, and it should all be an adventure, both in the getting there and in the arriving. Now we just have to organize the piles of gear that are still lying around above decks and below, make a final stop at the police dock to drop off our last minute trash and our pile of already-read books, and go.

Friday, December 14, 2007

Leg Two

Here is the barky, at low tide, ready to go to sea.

A few hours out we come across whales. The first notice I have of them is a trumpet blow off to starboard, a distinct B-flat with a lot of lung behind it. I look up and see the column of mist that the whale has left, then another and another. The whales start to lobtail and breach. Far away, but the telephoto lets me get decent pictures as we sail away from them at five knots. I think they’re humpbacks, though I’m not sure that humpbacks have such falcate dorsal fins.

These are two separate series of pictures.

After they’re gone I go below and smell whale breath through the open portlight in the head. Whale breath is invariably reported as foul, but from this great distance it smells faintly, and not unpleasantly, of pickles.

An exhausting night follows. Sails up and down, wind all over the place. Dodging ships across the Santa Barbara channel, their huge close shapes making me feel physical fear. The wind comes up to the low twenties around Point Conception, where we charge back to the north for half an hour to stay out of a ship’s path. Sailing upwind towards three oil rigs, I smell them clearly in the dark – like a book of matches that has been lit all at once and then soaked in water.

Alisa wakes up at 0100, but ships and sails need attention, so I stay on watch. After we cross the shipping lanes and pass San Miguel Island I struggle with the spinnaker pole in the dark, then struggle to get the autopilot to steer the unbalanced boat. Bugger.

I finally go down to the bunk with a course set to take us south of the Channel Islands. We’ll cross the Pacific Missile Test Range, which is marked on the chart, but we haven’t heard any training activity announced on the VHF. The range is not closed to navigation, so I figure all is fine. The Navy group that announces training activities in the area is called “plead control”. God knows why, but the name certainly suggests a hierarchy in the relationship between us and them. Whatever the case, plead control comes on the air two hours after I go to sleep, announcing “live fire exercises”. Commencing immediately. And directly in our path.

The wind has dropped again, so that we’re barely making headway under poled-out jib, and we won’t reach the training area for hours. I sleep briefly, then wake at dawn. The VHF is broadcasting an advisory for Santa Anna winds ashore, so now we have both the missile range and these strong northerly winds to consider. Our cruising guide warns us of the danger of Santa Annas, but I can’t get the marine forecast to find out what might be coming. We’re on a flat sea, the sail flapping in almost no wind, with San Miguel Island to port, three different shades of brown, bare and sandy. I try to form a plan. Everything in my head is slow with too little sleep. I make a mental list of things to do. Get jib in. Get pole down. Plot position. Get marine weather. Consult Coast Pilot and cruising guide for a suitable anchorage. I repeat the list to myself, again and again. Then I slowly begin working on one item and another.

We motor north through the Channel Islands towards Santa Barbara and away from the missile range, since the islands offer no obvious southern anchorages where we can hide from the Santa Annas. Alisa and Elias wake up and our day at sea begins. We cross the shipping lanes of the Santa Barbara channel again. I finally get a marine forecast on the sat phone and nothing more than NE 15-25 is called for. With relief we point the barky south. Neither of us wanted to go to Santa Barbara.

We pass three more oil rigs in the Channel. Like elephants, breathing fire from the tips of their snouts. Night finds us in the eastern part of the Channel, with dolphins riding our bow. I go forward and shine a flashlight into the water. The dolphins glow a pearly grey in the flashlight’s beam, like the souls of dead things trapped beneath the black water.

We pass L.A. in the early hours. Fog lies low over the water, so we see little evidence of the sprawling city. Planes hang in approach patterns over the airport, making stately strings of light in the sky.

At dawn we cross the shipping lanes south of L.A. Here's a tanker passing us to port. It’s all easier in daylight.

These southern waters are strangely empty. We see exactly one other sailboat between Morro Bay and San Diego. We make the nighttime entrance to Mission Bay, just north of San Diego, picking our way through crab pot buoys in the dark. And the next morning we motor the five miles south to San Diego. A blanket of smog greets us at the entrance.

And then we have this view of the city.

When we set off from Kodiak we had the early parts of our trip broken into two legs; one east-west leg that would get us to Haines, at the top of Southeast Alaska, and a long north-south leg that would bring us the length of the U.S. and Canadian coastlines, from Haines all the way to San Diego. So that second leg is finished, and we’re on the cusp of leg three, which will take us the length of Baja and into the Sea of Cortez.

We’re tied to the transient dock at the Harbor Police building, visiting family and getting things ready for our year of sailing the barky from the U.S. to Oz. This final stop in the U.S. gives me a chance to reflect on how much living we’ve packed into the last six months. Everything north of San Francisco seems like it happened to someone else, and Alaska seems like a different world. Back home we’d be skiing, and enjoying the round of seasons, and saying how quickly the fall went. Here time expands, it slows, and our constant exposure to new situations and lack of a set routine keeps us from glossing over the world and letting time, and life, pass us by.

Postscript:

I wrote the above entry a week ago, and we've now been in San Diego for more than two weeks. Aside from some visiting with family and socializing with a few friends we've been working that whole time, working as fast as two people trying to keep a one year old out of trouble on a yacht can work. We've pulled the autopilot drive for service, taken the injectors out of the diesel and put them back in, installed a new GPS, got the watermaker replumbed and working, been up the mast to retrieve faulty wind instruments, figured out how to retrieve weather charts from the ham radio, bought a huge array of spares and supplies for every system on board, and figured out all the arrangements for international travel: visas, insurance, health precautions, etc., etc. We are both a bit fried from the frenzy of doing all this while caring for Eli in the confined space of the barky. It's impossible to convey how slow things get when you're living on board with a baby and trying to work on the boat. When we began to see the bottom of the job list a few days ago Alisa said, "After all this work we're putting into getting the boat right, you know we're going to want to sail for more than a year."

We're ready for some stone-kickin' it time, maybe even a few of those Transcendent Moments that cruising is supposed to be good for. We had planned on getting some welding done in Ensenada, but are now planning on putting it off for La Paz and just enjoying the west coast of Baja without (we trust) too much boat work.

We'll be leaving the country for an indeterminate length of time when we motor out of San Diego Bay. I remember how visiting Ethiopia and Yemen twelve years ago gave me a fresh appreciation for the U.S., and I wonder if this stint away will have the same effect. San Diego, and much of our tour of the West Coast, have confirmed the worst of my opinions about the current state of affairs in the Lower 48. Maybe the wonders of Rapa, one of the strangest islands in the South Pacific, will be my solace. Or maybe it will be those spells at anchor when we row Elias ashore to the beach every day, and those weeks at sea in the trade winds, when we feel the peace that comes to people who sail out of sight of land in small boats.

Monday, November 26, 2007

Morro Bay

We're planning on leaving tomorrow, bound for San Diego. I had a strong image this morning of how much further down the coast we would have been if not for the daily mix of childcare and cruising, of how efficient and rapid we would be as just two adults afloat. On the other hand, if we'd stayed at home with Eli and put off cruising for the future, we'd be way behind where we are now. It's all good.

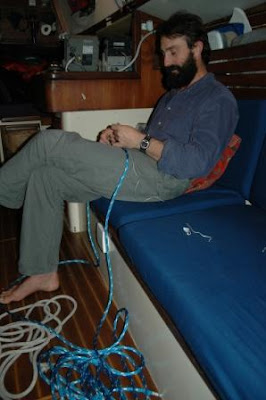

Here are a few Alameda shots, just to illustrate some of the jobs we were crossing off before we left.

Elias just clowned around.

Thanksgiving 2007

Alisa comes up to the cockpit, cross after standing watch half the night, and we jibe. After ten minutes the ship is closer and I realize we have jibed into its path. I jibe us again, towards the ship’s stern, and watch it slide past us, its massive bow wave clearly visible from a mile and a half away.

An hour later another ship comes along, then another. We realize that the ships are cutting the corner around Pt. Sur, which brings them in about 17 miles from land, close enough to cross our path. So we pull down the sails and motor in towards the coast to be free of them.

We close on the Big Sur coastline, brown hazy mountains coming strait out of the water, a place where few roads make it to the ocean. Four brown pelicans fly by us, perfectly imitating pterodactyls as they glide low over the water and occasionally flap their wings, one bird at a time. Last night was bitterly cold, too cold for bare feet, so cold that around midnight I retreated from the cockpit to the chart table below, and only came up every ten minutes for a look around. But now the sun is on the flat sea like beaten copper and I’m in shorts. Pt. Conception, still 150 miles south of us, is meant to be the division between the northern and southern California coasts, but with the pelicans and the strangely naked mountains behind the haze, it feels like we’re south now.

Alisa, meanwhile, has been rising to the occasion in the galley. At 1400 all hands gather for an onboard feast of yams, cranberry chutney, her famous mashed potatoes and Chilkat River sockeye salmon. We all have double helpings, including Elias, and Alisa and I inventory our causes for thankfulness, concentrating on the few and profound, rather than the many.

Wednesday, November 21, 2007

Gone

The weather forecast is great for the next few days, north winds 15-25 knots. We plan to fuel up and anchor the night off Sausalito, then head out the Golden Gate tomorrow morning.

Reading "Lucky Jim", by Kingsley Amis. Brilliant written comedy, great depiction of individual pathos in the early modern age. Also a great contrast with Evelyn Waugh's "Sword of Honour" trilogy in terms of the development of English society through and after World War II.

Came across a passage in there that very well illustrates the Once in a Lifetime theme:

"...here he was, quite able to fufil his role, and, as with other roles, the longer you played it the better the chance you had of playing it again. Doing what you wanted to do was the only training, and the only preliminary, needed for doing more of what you wanted to do."

Saturday, November 17, 2007

Walkin’

Elias began walking two and a half weeks ago. Baby’s first step is of course supposed to be one of the special moments in parenthood, and Elias’ lived up to those expectations and exceeded them. It was like hearing for years about how spectacular Geographic Harbor is, then going there and finding that the descriptions you’ve heard don’t do it justice. He started walking one day at the housesit in Berkeley, and when I got back from the boatyard he was trotting in circles around the ottoman, holding on with one hand to keep his balance. Every now and then he launched out into open space towards Alisa, who was kneeling two or three baby steps away. His walking was really just a controlled crash, as he managed to totter on his unsteady legs for a moment before collapsing into Alisa. The redeeming part was the pure joy Elias was expressing, the huge smile that filled his face and the giggly laughter as he tried his new trick over and over, his little body overflowing with the excitement of what he could do, his head thrown back in a good imitation of ecstasy after every crash into his mother’s arms. What fun.

For the first week or so he walked just like an orangutan, with both hands held out front, up high over his head for balance. He’s still very unsteady, and has collected a prime series of bruises from his various encounters with fixed objects, most notably the floor. Our boy seems to lead with his head. Notice the cut temple and rug burn around the eye in the picture above.

Still in Alameda, but getting close to leaving. Throwing down for a new ham radio today, having decided that the Kenwood that came with Pelagic is too geriatric to make the trip. Mounted the Monitor windvane on the stern yesterday, fresh back from the shop with a bunch of new welds, two new diagonal cross braces and a new pinion gear. The people at the shop were very helpful, throwing in used parts and factory seconds at no charge, and this most useful of all optional devices on the boat is strong and (hopefully) ready for another 17 years of steering Pelagic.

Saturday, November 10, 2007

Map of the Trip Thus Far

Also, the map let us calculate the length of our voyage so far - looks like we have covered about 2,800 nautical miles.

View Larger Map

Wednesday, November 7, 2007

Always Getting Ready

After Aquatic Park we motored across San Francisco Bay to Alameda. We got great views of the City from the water, and traveled under the Bay Bridge, which is in the background below.

San Francisco Bay is incredibly small (the main part of it, anyway, barring the estuaries and rivers that branch off in different directions). It’s only a few miles from San Francisco to Oakland and Alameda. The entrance to the ditch separating those two cities hosts a big container-loading facility, seen below. As we drive borrowed cars around the East Bay those cranes make a great landmark, and Alisa and I are quietly treasuring the expectation of the day when we’ll motor past them on the way out of Alameda.

Many of the containers loaded by these cranes arrive or leave the port on trains, and one of the very best parts of Alameda for me is the sound of the train whistles blowing in the yards across the ditch in Oakland. We hear them at night when we’re lying in our bunk. Normally when you hear train whistles they’re doppler-shifted by the velocity of the train, and there’s only the one whistle, disappearing into the distance and sounding lonely. But the trains in Oakland aren’t moving fast, and there’s a lot of them, so their whistles sound conversational and friendly. I love it.

Can’t say I love much else about the East Bay. Our time here has made us both lonesome for Alaska, and a bit shocked at the life that so many people put up with in the Lower 48. The aesthetics of the landscape in Berkeley-Oakland-Alameda are just disastrous, and the filthy air and freeway-centered lifestyle are too grim for words. This is a place where people commune with nature by buying shampoo containing botanicals and algae extracts from upscale grocery stores that are so crowded that you literally get shopping cart traffic jams. The East Bay is, in a nutshell, a poxy shitehole. (I’ve just read Trainspotting.) No offence to the wonderful people who live here.

On a brighter note, we have reunited with Elie and Marie in Alameda, friends who we met when they spent the winter in Kodiak on their sailboat. Now they have a new boat, and a new crewmember, four year old Jules. They have been living in Alameda for those four years, saving up money and getting their boat ready to cruise for the next 20 years. Elie and Marie are very experienced sailors who have had fine adventures in remote places in the Pacific, and I find talking with them to be wonderfully reassuring and informative. As opposed to all the marina experts whom we’ve met in California, Elie and Marie have embraced cruising as their life, and they have a frugal and realistic take on cruising that really contrasts with the spend-another-grand-at-West-Marine approach that we more often encounter.

We spent a few days tied up at the docks of two yacht clubs in Alameda, where we met some very friendly people, and then we made the decision to haul out here, instead of waiting for San Diego or Ensenada. We were helped out by a timely housesit for my sister’s good friends Jen and Ben in Berkeley, so we could tear the boat apart without keeping it baby-proofed for Eli. And tear it apart we did, getting after both routine maintenance and some pesky problems that we didn’t want to deal with in Kodiak, where getting sailboat supplies is so hard. Here are pictures of me painting the sheer stripe, Alisa greasing winches, and the interior of the poor boat in mega-project mode.

We were in the yard for twelve days, working hard every one of those days. What a joy to finally launch. We’ve got those twelve days of work behind us, but there are still plenty of jobs that we’d like to cross off the list before we leave the country. That’s where the “Always Getting Ready” part comes in. The topic of boat maintenance is the dread curse of writing about the sailing life. No one can make stories of fiberglassing rudders or replacing bilge pump hoses entertaining. But again and again people living on sailboats who fancy themselves writers decide to go on about these topics, falsely assuming that others will find their boat projects interesting. I have manfully resisted the temptation to write about maintaining the barky on this blog. But now, since we’ve just hauled out and are in the midst of an avalanche of in-the-water jobs, I will indulge myself briefly.

And so, in brief. We have put a crushing amount of work into Pelagic during the four years we’ve owned the boat. A truly overwhelming amount of work. This is a normal state of affairs for anyone going cruising on a budget. So while we’re lucky to be doing this trip, as lucky as anyone is who can chuck it all for a few years and savor a life lived at sailing speed, please don’t think that it’s just luck that has gotten us, or any other cruisers, to the point of casting off the lines and heading out for a year or three. There’s luck involved, and the ability to organize your life around a vision, but also more work than many of our contemporaries can imagine.

Things on boats are always breaking. That’s a normal state of affairs, and as boats have become more complex, the number of things that can break has increased. As we sailed down the west coast, Alisa and I kept a list of boat jobs that we’d like to get done before we leave the ready availability of parts in the U.S. and begin our trip across the Pacific. The list runs to 80 jobs. We’ve put all that work into Pelagic over the last four years, and we’re still not ready. We plan on another slug of boat work in San Francisco Bay, then another in San Diego, and another in Ensenada. Then, hopefully, we’ll have the boat at a level of readiness that will allow us to drop back to say, 20 hours of maintenance work a week as we sail down the Mexican coast and across the South Pacific.

We’re both pretty tired of being in Alameda, and we suspect that we’ll like San Diego, our one other chance at the services of a major city before we leave the U.S., even less.

We’re getting very excited for Mexico, and the delights of the South Pacific beyond, and realize that we are again reaching a point, just like the one we reached when leaving Kodiak, where we’ll have to work hard to get ready and then just leave, regardless of what jobs are or are not done.

Sunday, October 21, 2007

Homecoming

Cruisers up the coast in Eureka had told us about Aquatic Park, a little anchorage protected by a curving sea wall off the north shore of the San Francisco peninsula. It’s administered by the National Park Service and 24 hour anchorage is free for sailboats. We pulled in after our Flight-of-the-Valkyries entrance under the Golden Gate bridge and found four or five cruising boats already anchored and a fleet of smaller boats riding at moorings.

The anchorage was much much more crowded than anything we are used to from the north, and we took two tries to find a spot that we were comfortable with. I still find the geometry of anchoring difficult to predict, and am often slightly surprised at where we come to rest after reversing back on the anchor. In one of our passes around the anchorage a guy on another boat saw the hailing port on our stern and asked if we sailed all the way from Kodiak. “And did you plan to show up today?” he asked. “What’s today?” I asked back. “Well, it’s Fleet Week, and there’s going to be an air show tomorrow.”

Our second try gave us a reasonable anchorage, though much closer to the sea wall than we would have chosen in the absence of other boats. We stared up at the apartment buildings marching up Russian Hill and the giant Ghirardelli sign above the waterfront. San Francisco! It was hard to believe that we had sailed all that way from Kodiak. San Francisco is different enough from Kodiak to feel like our first exotic port of call, and in a way that night on the hook in Aquatic Park was the first time that we felt like cruisers. Instead of sailing through the comfortable expanse of Alaska, or traveling down the Washington and Oregon coasts to get somewhere else, we had transported the family and our little home all the way to this distant corner of the world where widely-held assumptions about the nature of life are dramatically different from the ones we operate under back on The Rock.

The next morning we rowed ashore to a little patch of beach between the dock where the Park Service displays historical ships and the two swimming clubs that have operated in Aquatic Park since the 19th century. Signs at the entrance to Aquatic Park warn boat operators to watch out for swimmers, and we soon found that this was no idle warning. Two swimmers crossed our bow when were looking for a good anchoring spot, and the splashing of marine mammals from order Primatea was a regular sound for as long as we stayed in the Park. They mostly traveled in twos, all wearing swim caps and goggles and some wearing wet suits. Nutters, I thought at first. But then it occurred to me what a neat local tradition it is to swim in the bay, with the long-established clubs for that purpose, and also what a powerful link between the City and the Bay, this constituency of people who regularly immerse themselves in the waters that are the reason for this city’s existence.

We pulled the dinghy up the beach and joined the crush of tourists on the dock to brush the sand off our feet and put on our shoes. Then I hoisted Elias into his backpack carrier and we set off into the City, destination North Beach.

I was pleasantly surprised at how easy it was to find my way around. I was quickly showing Alisa landmarks from my life 17 and 18 years ago. Gino and Carlo, the bar where we shot eight-ball at the back table for fun while the good players shot nine-ball at the front table for money. Grant and Green, where we used to sit outside on the sidewalk, drinking bottles of Gallo and listening to the music from inside the bar. The bakery that set stale loaves of bread in a barrel just inside the back door, free for the taking. Alisa and I gave ourselves the great treat of choosing from all the available cafes a spot for our lunch. The whole part of North Beach culture that revolves around life at the table is nothing that I partook in during my residence in the city. I was perfectly disposed to enjoy our meal – the company of someone I love, the appetite of a good walk with thirty pounds of descendant on my back, and the excitement of returning to my former haunts with a new sort of life in hand. My glass of wine had the effect that novels occasionally depict for alcohol, but which I rarely feel: it brought an edge to my happiness, and made the situation sparkle just a little more. Alisa and I talked and talked. Elias, woken from deep slumber in the backpack carrier for the event, cooperated by sitting subdued on my lap, tamely eating proffered tidbits.

We made a visit to City Lights bookstore, a place I’ve only been in about a hundred times, though not since I left the city to hitchike to Alaska in the summer of 1990. Alisa found a book of Gauguin’s letters (setting up our new South Pacific reading theme), I found the third book of Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy (the whole turning out to be much more uneven than the standard suggested by the first third of the first volume, but with illuminating themes; not the sort of World War II fiction that you come to expect after reading The Naked and The Dead) and, for both of us, Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast, simultaneously a great depiction of the sailor’s life and of pre-1849 California.

City Lights in its contemporary incarnation matched delightfully well with my memories. This was true of San Francisco itself. So many changes have come along since I lived here. AIDS is a treatable chronic disease. Cell phones have arrived, as has the digital age. The dot-com explosion and real estate run up have been here and gone. (I used to moan about paying three hundred dollars a month in rent when I lived here.) We even saw, on our trip to the East Bay a couple days later, that the Embarcadero Freeway is gone, opening the eastern part of the city to the sight lines of the Bay that are one of the delights of San Francisco.

For all these changes, the City feels like it always did. The streets look the same, the sound and smell and feel are the same. The same landmark businesses that I remember are there, and I could find my way around with little reference to the map.

We returned to the beach burdened by bags of groceries. The air show had begun, and thousands of people had congregated on the shore around Aquatic Park to watch. The little beach where we had left the dinghy was now carpeted with spectators, one enterprising fellow even sitting in our dinghy to watch. He was very nice about helping us pull the boat down to the water, and families made a path for us. A little chop had come up and was breaking on the beach. We watched the waves and timed our departure, getting baby, baby carrier, backpacks and groceries into the dinghy and away between wave sets, all with hundreds of spectators on the beach and pier above. No problem.

The next day we again rowed in and set off into North Beach, walking up and over Russian Hill and enjoying the neighborhood feel of the City’s quieter streets. We shared the daydream of someday having a pied d’terre in San Francisco. I could see the rooms in my mind’s eye, with their view of the Bay on two sides, the modern furniture, spare décor and groaning bookshelves. The delights of thinking about the ideal future! We took the antidote for living in the future by next talking about how wonderful it would be to someday visit the city in our own yacht, so that we could anchor in Aquatic Park and enjoy the urban delights before retreating to the privacies of our floating home every evening.

Before we left Kodiak I had ruled out a visit to San Francisco, thinking that it wouldn’t be much fun with Eli. Wrong again, and another example of the little ways that the actual trip has differed from my mental picture during the planning stages. Elias happily rode through the city on my back, taking in all the new sights as a matter of course.

Our mission this day was a visit to the first place I lived in San Francisco, in the Tenderloin neighborhood at O’Farrell and Larkin streets. This was, when I lived there, a very scummy place. Before we arrived I wondered if gentrification had moved in. We walked through upscale Union Square, and I told Alisa about my job as a street sweeper for the Union Square merchants’ association. (I was fired for parking my broom and repairing to the delights of North Beach while on the clock.)

As we continued up Geary Street from Union Square things progressed towards the unfortunate end of the seediness gradient. On my actual block things were very gray and dingy. Three young women came out of the door of my building. With their odd haircuts and easy assurance on the street they might have been friends of mine, twenty years ago. There was a gate blocking off the steps up to my building, and a similar gate on every building on the block. The street stank of urine, as always, and the tiny city park on the corner was locked up. The modern apartment building across the street from my old place was still there, but that appeared to have been the high-water mark for gentrification. The Great American Music hall was still next door to my building, and the Mitchell Brothers’ Theater (“the Carnegie Hall of American public sex”) was still at the end of the block. It felt scummy, but not dangerous, even with my completely atrophied street sense. But on our return to the boat I took us north up Polk, through an area that I didn’t remember well. The vibe got worse for a few blocks before it got better. We were presented with living-breathing examples of several urban archetypes. The Statuesque Transexual. The Strung Out. The Clearly Mad. The Young, Fresh Out of Prison and Soon Headed Back. The Toothless and of Indeterminate Sex. The Runaway Hustler.

Elias apparently continued to take it all in from the vantage of my back. Later, restored to the comforts of above-mentioned yacht, Alisa said, “I don’t think I need to see any more of your old apartments.” So a trip to my old pad in the Lower Haight is off.

Too bad in a way, because that room in a shared apartment is where I put maps of Alaska on the wall and dreamed about long journeys on foot across treeless Arctic mountain ranges, clean and vast and innocent of the contemporary world. I didn’t want ordinary backpacking trips, I wanted capital-A adventures that only Alaska could offer. That was another dream that I acted on, and I did find myself a new kind of life, and adventures on a fairly grand scale. And after a while it was Alisa that I was doing ski trips with, traveling self-supported through the crystal perfection and daunting cold of Alaska in winter. And, just as is the case with our travels on Pelagic, acting on the Alaska dream changed the dream, and I found myself immersed in a new kind of quotidian life on the other side. So how fun to return to this city that grew stale for me almost twenty years ago, to return with wife and son and sailboat, in a condition that I only could have dreamed of, and did, those years ago.

Monday, October 8, 2007

San Francisco

After all the talk from other cruisers in Eureka and Newport about how short the weather windows are, and how bad the forecasts, we had a great two days’ trip down from Eureka. The bar at the Humboldt Bay entrance was much better behaved than it had been the day before when we turned around. Out on the ocean we soon came into black-footed albatrosses, and found that the eight-foot swell that had me concerned at the dock was absolutely no big deal at all.

A low was forecast to bring rain and cold to northern California twelve hours after we left. All that day and the next we watched foreboding clouds gathering to the north of us and wondered if we would beat them south. We sailed wing and wing and motored when the wind failed.

After a day and a half we found ourselves poised for a wee-hours arrival in San Francisco, which was clearly out of the question. At first we thought of heaving to outside the entrance and waiting for dawn. But rather than dealing with the vagaries of floating around on the ocean with the concerns of nearby land, unpredictable currents and abundant ship traffic, we decided to pull into Drake’s Bay, 25 miles north of the Golden Gate and named for Sir Francis, who anchored there in 1579, if you can imagine that. Speed and distance showed us arriving at Drake’s Bay after midnight. Our standing rule is to not enter unfamiliar anchorages and harbors at night. But Drake’s Bay is a broad bight, easily entered, and seemed much the easier and safer option for the remaining dark hours. I had slept from 0130 until 0600 the night before, and had been on watch the whole of the following day with only a twenty minute nap while Eli was eating dinner. So the allure of deep sleep in a secure anchorage was strong.

Alisa stayed up after putting Eli to sleep, instead of immediately going to sleep herself as she usually does when we’re at sea. It was a real treat to be up together at night. She dozed in the cockpit until a northbound fishing boat crossed close in front of us and made me nervous. Wouldn’t answer a hail. We’re getting more at ease around the denser traffic of the west coast. But there is still something nerve-wracking about passing close to another vessel at night, something about the tricks of perspective in the dark and how lights seem to hover right next to us, close but we’re not sure how close, not moving away nearly as quickly as we would expect. The fishing boat did just that, clearly showing us their red light, meaning that we were looking at their port side, but once they were abeam of us they just seemed to hover there, without getting farther away, until Alisa wondered out loud if they had changed course towards us. Spooky.

We simultaneously worked the radar, GPS, depth sounder and chart to make our way into Drake’s Bay. Giant ships lumbered off to the north in the shipping lane offshore of us, heading off on the great circle route from Oakland to Asia and showing us the green lights of their starboard sides. There was one other boat already in Drake’s Bay when we dropped anchor under a sky rich with stars, the Milky Way bright enough to leave a shine on the water. The other boat’s anchor light looked to be at the top of a mast, and we wondered if it might be one of our friends from further up the coast.

Elias woke up screaming as we were making the final approach into the bay. Alisa nursed him and he calmed down, but then he wouldn’t go to sleep for either of us. It was after 0100 at this point, and I had been in the cockpit for 18 of the last 24 hours. I was bushed, grumpy with Alisa and cross with Eli. He finally fell asleep on top of me, behind the leecloth in the port settee. I woke up at three o’clock with Elias completely zonkers and my right arm asleep from cradling him. I carried him up to his forward bunk, had a look around outside and then fled back to the solace of the bunk. My alarm went off at 0530, before there was any suggestion of dawn on the horizon, in time for us to make the morning flood through the Golden Gate. It was clearly an unreasonable time to be awake. I briefly consulted with Alisa about the necessity for an afternoon flood to follow that of the morning, and what an excellent idea it would be for us to catch the later, not the latter. Without completely waking she agreed.

We all had a wonderful sleep-in. It qualifies as one of the “no-duh” observations of our new cruising life, but our state of rest has an overweening control over the degree of warmth with which we regard our fellow Pelagics. I’m occasionally amazed at the scowling beast that I’m so successfully imitating during some sleep deprived moment when Elias is acting the screaming one-year-old.

When we woke the other boat was gone, and the white cliffs and sere tablelands of the bay were revealed. Drake’s Bay is behind Pt. Reyes, a place that I picture as being part of the rush and hustle of California. But the scene from the water was beautiful, with a few compounds of barns and large houses tucked here and there in the folds of the hills. Combined with the spectacular show of stars the night before, it gave me faith in the idea of pockets of natural refuge tucked here and there in California, even so close to the city.

The wind was also blowing when we woke up, gusting as high as 37 knots with whitecaps pushing us away from the beach. After pancakes and coffee we enjoyed a great rip-snorting sail down the coast, effortlessly making seven and a half knots with a double-reefed main and poled-out 100% jib. You can see the vanguard clouds of that low in the second picture below. They followed us all the way to San Francicso, but never quite caught us.

Wednesday, October 3, 2007

Disbarred

Eureka sits on Humboldt Bay, a glorified estuary with an entrance guarded by a bar that sometimes makes the prevailing northwesterly swell break. With a good coastal forecast in hand for the sail to San Francisco, we called the local Coast Guard station this morning for a report on bar conditions. Their answer was a six to eight foot swell with occasional ten footers, rolling in the channel and breaking on the middle ground, potentially hazardous conditions. There are two jetties that protect the entrance, and the channel for navigation is right against the southern jetty, with the middle ground shoal occupying the middle and northern area between the two. We decided to go take a look for ourselves. We found surfers doing their thing on the middle ground, and current and foam swirling around in the channel. Fishing boats were making it out in the relatively smooth channel, but it was all too intimidating for us with our inexperience of river bars, and we turned around and tied up again at the dock that has been our home for the last four days.

Alisa had taken a Bonine against the four hours that we expected to be motoring with the forecast eight to ten foot swell on the beam, and she found herself severely backwinded all during the afternoon, fighting off the chemical drowsiness. “It’s so hard with these short trips,” she says. “Just when you’re getting into the rhythm, you go in, then you go out and have to get your sea legs all over again.”

We’re having our first experience with the group approach to interpreting weather forecasts. The forecast hasn’t been entirely perfect since we’ve been here, with that eight to ten foot swell rolling down from Alaska every day. The three or four cruisers here all talk about the weather, and ask each other when they’re going. It can be useful to talk things over, but it’s also easy to build your plan based on the prevailing group opinion rather than your own interpretation of available information. We’re pretty sure that we’ve happily dealt with much worse conditions in the past. But when you’re sitting in the harbor and not too experienced it’s easy to get intimidated. I haven’t been helped by the NOAA website I found that explains the distribution of individual wave sizes for a given significant wave height (defined as the mean height of the highest one-third of waves in an area, the number that the forecasts predict). Individual wave heights follow a Rayleigh distribution, with very big individual waves occasionally coming along. So, for a ten foot significant wave height at a period of eight seconds, you can expect a 19 footer (or bigger) to come along every 2.2 hours. Whoa. Ignorance may be bliss.

The forecast is for the swell to be a foot or two lower tomorrow, and we’ll take another look at the bar.

Eureka is blessed with good used book stores, and we made another fruitful visit to them on our unexpected day ashore. I began Men at Arms last night, the first of Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy. By the time I reached page 40 I was loudly wetting my pants, filling the little salon with a variety of guffaws and snorts while Alisa read through the finish of Breakfast at Tiffany’s with the look on her face of someone doing something self-improving. Evelyn Waugh is as funny as anyone, even Mark Twain, and the English social milieu that he has to work with is delicious raw material for an American reader. Bought three more Waughs today, including the second book in the trilogy. Standing watch is a grand time for reading. I’ve been plowing through the books on our way down the west coast. Good stuff early on, and then when it’s after midnight and I’m too sleepy to give Ryszard Kapuściński the attention he deserves, I start reading books about sailboat maintenance.

Walking back from the bookstores we are surrounded by the traffic pulsing around the historical downtown. So loud for such a small town, everyone driving fast, with looks of competence and boredom and contempt on their faces. Pedestrians are tattooed and pierced and sunglassed and possessed of extravagantly palpable street attitude. In Eureka. Elias, riding in his pack on my back, partly thaws the game face of many, giving me the weird experience of over and over watching the blank scowls of approaching strangers waver into an almost-smile while looking at a point just behind my left shoulder. The idea of a “stranger” is much more threatening here than in Port Townsend, and entirely foreign to any social idea that operates in Kodiak. In P.T. a stranger might conceivably be a friend that you haven’t met. You don’t get that idea in Eureka.

We walk down to the boardwalk along the river. Eureka is a town that ignores its riverfront. Boarded-up buildings, empty lots and graffiti-ridden diesel locomotives abandoned and surrounded by chain link fence separate downtown from the water. The boardwalk was an apparently expensive attempt at civic recognition of the river. Its comfortable benches and engineered railings that follow the organic curve of the riverfront have been abandoned to the halt and lame, the outcast and the desperate. A malnourished cripple shuffles back from his trip to the mission. A mother holding a sixteen ounce Budweiser and a cigarette in the same hand tells a little girl, “Angel, pat that dog on the back end, not the front.” Musicians with matted hair and missing teeth sit on benches in groups and strum guitars to no audience but each other, nodding their heads in sleepy unison. A shirtless man slumps against a woman, both perfectly immobile in apparent stupor. Everyone else wears more than one pair of pants and multiple hooded sweatshirts against the cold that comes each night. A hundred feet away pelicans fly in low formation over the water. Harbor seals glide up the river, their heads and backs two separate bumps in the water’s surface. Cormorants and loons dive for their supper. Smoke from the pulp mill blows across the river in two giant plumes. A good sailing wind.

We’ve been enjoying meeting other cruisers on this coast. Again, it seems that the more experienced are long gone with the season, and we’re with the straggling rookies. Early on anyone traveling in a sailboat seemed like a soul mate to us for their pure novelty and superficial resemblance to ourselves. But now I’m starting to see the vast diversity even within the fairly narrow demographic that cruisers represent (white, older than young, bent enough to want to live on a sailboat). Not all of them are Our People, but we feel a very strong camaraderie even with those we’re not simpatico with. It’s the same ocean that we’re all traveling on, and we’re all bringing an imperfect set of skills to bear on the task.

* * *

Will finish by saying what an inexpressible joy Elias has become when he’s on a happy jag. He’s not walking or really talking, but he cruises around the salon incredibly quickly, leaning on one settee and then the other, and he has the initial consonants and vowels of a dozen or so recognizable words. This self-directed motion and beginning verbal expression lets him go on long tears of purely joyful exercises of personality. He grins and laughs and slams his head into the settee cushions out of his overwhelming happiness. Then he picks up his yellow ball and says “buh!” twenty times in ten seconds as he bangs it into the sole. There is no happiness like a one year old’s.

Monday, October 1, 2007

Comments

Eureka!

This stretch of the coast presents us with a bit of a chess match – harbors are scarce, so we listened to the VHF forecasts carefully and plotted the distance to different safe harbors as a series of lows approached. We had a great two day trip down from Newport, Oregon, logging 145 miles straight-line distance noon to noon on the first day, with a 25 knot northerly that had us cooking along at seven and a half or eight knots for hour after hour. Only blot on the record was tangling with a ship at two in the morning. Good lesson learned – we were concentrating on a sail change and weren’t as aware of our surroundings as we should have been. The ship ended up less than a mile from us (or us less than a mile from them?), and we had a bit of a chat on the VHF, the tug standing by for them coming up and giving us the ship’s name (the Jeannie Star, of all things) when they wouldn’t respond to a hail by coordinates. We had a full moon, and there’s nothing more intimidating than being in a small boat and seeing a ship come progressively closer until it turns from a group of lights to a clearly visible silhouette looming above you and you’ve been so intent on getting the spinnaker pole down that you’re not quite sure of their course or what action you should be taking to get clear of them.

* * *

We had a great stay in Port Townsend after our soggy passage down from Baranof Island. Got lots of pressing jobs done on the barky, including an apparently successful re-seal of the cap rail forward and some hardware. The deck leaks that denied us the use of half of our boat on the way down from Southeast Alaska appear to be a thing of the past. We also had a good time visiting with different friends while in P.T., the highlight perhaps being a visit from our good friends Jennifer and Jason and their growing brood. Jennifer and I and our friend Jebbers were roommates in Anchorage the winter that Alisa and I started dating, and we have great memories of that winter when we had jobs that were semi-respectable and interesting and a great group of friends for an endless round of x-country skiing and bar hopping and ice skating and parties. As I was taking this picture of Jennifer and her two kids and Alisa and Eli all sitting together in the salon I was thinking about that carefree winter and how improbable this picture would look to us then if we’d been able to see it, and also how inevitable and necessary. God, what a jump forward the last ten years have seen!

This is Alisa provisioning for the trip south from Port Townsend. Order will be constructed from this chaos!

When we planned this part of the trip from Kodiak we imagined that we would just get one hundred miles offshore from the Strait of Juan de Fuca and blaze all the way south to San Diego in one mighty whack. But once we were actually beginning the run down the west coast with the dual overriding tasks of taking care of both Eli and the barky while on passage, we figured why not stop into Newport after two days sailing from the Strait and catch up on sleep. Which we did, and we had a great time visiting with Alisa’s colleagues from the local NMFS lab and our good friends from Kodiak, John and Patty Mahoney, who are currently living in Eugene. When I was telling John about our tough trip down from Baranof Island, I told him that part of the difficulty was just being new to passage making, and that we expected things to get easier as we gained experience. “Oh, if only that were true,” he answered. Here’s the entrance to Newport.

Newport is the southernmost port on the West Coast where we have resident friends, so we’re going to have to begin to make some new friends as we go. Conveniently, we find that we’ve joined a fairly widespread migration of cruising sailboats heading south for the winter.

When we pulled into Newport there were four other boats at the transient dock that were also headed south. All were about our size, all looked shipshape. Two of the boats pulled out the next day, both with rookie crews that were suffering their share of lumps on the way, but were gamely carrying on. Pacific Northwest boats seem to have a tough go of it when finally setting off on the big trip, since they have to jump into ocean sailing right away. We were looking for a San Francisco chart in the local marine supply store when we met a young couple on the perhaps inaptly named Tenacious, a lovely ketch with well varnished wooden spars that was tied up two slips away from us. For two years they had been living on board in Astoria, Oregon and preparing for a cruise to Baja. “We’re having a change of plans,” the woman explained to me, “and we can give you some charts for south of here.” They were both in their late 20s or early 30s, and were, improbably enough, wearing their inflatable PFD/deck harnesses in the store. After making it 90 miles south from Astoria they had decided that sailing was too slow a way to get to Baja, and they were making arrangements to leave the Tenacious in Newport for the winter and fly down to Baja. One of the charts they gave us was for the Humboldt River and Eureka, which was a huge help in getting in here.

Alisa chatted up the older couple from the next boat over at the dock and came back to Pelagic with their story. They had the boat built in P.T. and spent untold hours preparing for a long cruise, including doing all their own canvas work and making their own sails. On their way south lost all electric power, which put the kibosh on radio (no communication), chart plotter (no navigation, except for the no-detail small-scale charts they carried as backup) and engine (no go for the get-over-the-bar-and-go-up-the-river routine that characterizes every port in Oregon). And he broke a rib in a fall and developed possibly complicating blood clots. The Coast Guard towed them into Newport and when Alisa met them they were waiting for him to heal up and eyeing the approaching end of the season for getting out of Oregon. Dreams of palm-shaded anchorages and the earthly version of paradise were fading into a reality of a winter tied up behind the Rogue brewery in rainy Newport. But they were showing a brave face.

And when we arrived in Newport there was a message on our cell from Karla, who Alisa had met in P.T., and who was sailing south with her dude. They anchored next to us in Neah Bay, the last stop in the Strait of Juan de Fuca for outbound boats. In her message Karla said they’d gotten beaten up on the outside coast and were in Willapa, Washington and were reconsidering their trip south.

It’s been quite an eye opener to see so many sailing dreams coming so quickly to grief. We’re on the very end of the good season for making the passage south. The more experienced and more organized cruisers are likely already gone, with the less sure hanging on at the back end, and the steel door of the season liable to slam shut with the first week-long delay from gear failure.

We, meanwhile, are feeling with every fiber the necessity of getting south. When the north winds blow and the foam builds on each side of the bow as we surf down the waves with the jib poled out and the main reefed and prevented and herds of Pacific white-sided dolphins all around I exult in the progress we’re making. But this is also one of the great foggy coasts of the world, and when the cold mists inevitably follow the beautiful sailing days and we stand watch down below by looking at the radar screen because we can’t see a damn thing on deck, and we wear three layers during the day and four at night and put Eli to sleep wrapped up in a cocoon of polar fleece, I know that we’re not nearly so south as we need to be. Alisa and I have both spent our adult lives identifying with and reveling in the north, but now we’re bent on palm-fringed dreams of our own, and the south is the place for us to be.

* * *

We listed out all the jobs that we’d like to get done during our impending haul-out in order to have the boat ready to set out across the Pacific. The list runs beyond 80 items, and we figure a month will be needed to get a reasonable minority of that work done. It’s all routine maintenance and small problems that we’ve been meaning to get to forever. I figure that a solid month of maintenance will be our annual routine for as long as we’re cruising Pelagic, in addition to the few hours here, few hours there routine that makes up much of our time afloat. Right now we’re trying to figure out where we might haul out.

Meanwhile, if you’ve read this far then you’re enough of a fan to care that a story about our Alaskan sailing is in the October issue of Cruising World magazine.